Ashley Bryan

Ashley's

Timeline

1923

Ashley Bryan was born

in Harlem, New York in 1923

Ashley was the second of six children who were later joined by three cousins in his family’s crowded Bronx, New York apartment. His parents were immigrants from the island of Antigua.

Ashley began drawing and painting as a small boy. A printer by trade, his father was able to supply Ashley with left-over special papers for Ashley’s endless flow of artwork and drawings.

1928

First Publication

Five year old Ashley Bryan’s first book received exuberant praise from his kindergarten teacher and parents, all of whom marveled at his success as “author, illustrator, publisher and distributor” of his very own alphabet book.

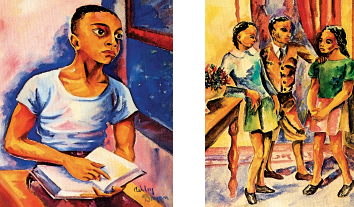

Nephew “Boots” (left) and Sister Emerald and Cousins (right), painted by Ashley with tempera at age 12

1938

Graduation

and on to Art school

When Ashley applied for scholarships to art schools at 16, he was told that his portfolios were among the most impressive ever submitted. Yet, his applications were denied, since, “It would be a waste to give a scholarship to a colored person.”

Ashley was eventually accepted to the tuition-free Cooper Union School of Art and Engineering in New York City—where “they did not see you”— solely on the basis of his exam portfolio. In 1940, he began studying sculpture, calligraphy, design, book illustration and painting.

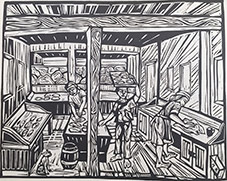

Cooper Union drawing assignment, Ink gouache on paper, June, 1942

1943-1946

WWII

and the Segregated US Army

cIn May of 1943, Ashley was drafted out of Cooper Union into the segregated 502nd Port Battalion for training as a stevedore. White, mostly southern officers were assigned to Ashley’s company. Their attitudes in dealing with black soldiers were often disrespectful; Ashley discovered that German prisoners received better treatment than the black soldiers. Hiding his art materials in his gas mask, Ashley drew everything he experienced, including sketches on Omaha Beach marked “D-Day plus 3.”

Private First Class Ashley Bryan, of the 270 Port Company, 502 Port Battalion of the Segregated U.S. Army, 1942

1946-1950

Columbia University

Ashley enrolls at Columbia University, graduating in 1950 with a BS, Cum Laude. Both his army discharge papers and his Columbia degree were signed by Dwight D. Eisenhower.

1946-1949

Seeking Answers

First Vists to the Cranberry Isles

The few soldiers in Ashley’s unit who survived the war came home in "dribs and drabs" as space allowed for the segregation of black soldiers on returning ships. In 1946, Ashley returned to Cooper Union to complete his art studies. He was offered a summer scholarship to the new Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture in central Maine, which was attracting the strongest artists in the country. There, Ashley first visited Acadia National Park and viewed the Cranberry Isles, later to become his permanent home.

Cranberry Islands, first visit, oil and paper, 1947 (left) and Skowhegan figure drawing class on Lake Wesserunsett, Central Maine, 1946 (right)

1950-1953

Aix-en-Provence

The Casals Years

In 1950, Ashley went to France to study art at the Université d’Aix-Marseille in Aix-en-Province. The following year, exiled world-renowned Catalan cellist Pau (Pablo) Casals, agreed to break his vow of silent protest against Franco’s fascist dictatorship in Spain. Ashley and a group of fellow students traveled from Aix to Prades, France, to hear Casals play in honor of the 200th anniversary of Bach’s death.

The event had a profound influence on Ashley in his own struggle to heal and move on from the war. For the next three years, Ashley returned to Prades for the annual Casals Festivals to hear and sketch the musicians. To this day, Ashley describes the experience of drawing the musicians in Prades as an “opening of my hand to the rhythms” that would form his signature style in all his artisitic expression from then on.

Ashley with Robert Hellman, Aix-en-Provence, around 1952 (left) and Drawings of Pau (Pablo) Casals, around 1950 (right)

1953-1956

Re-entry

New York and Maine

Ashley returned to the Bronx in 1953 and began teaching art full time. He continued to spend summers on the Cranberry Isles. During his years in Aix, Ashley had gotten to know many expat intellectuals studying and/or living in France. These acquaintances included numerous people who were introduced to the Cranberry Isles by Ashley.

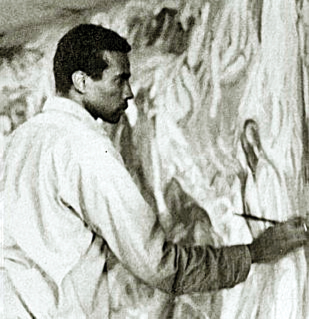

In 1956, Ashley returned to Skowhegan, having won an annual competition to paint one of the frescoed walls in the South Solon Free Meeting House. Other walls were frescoed by Sidney Hurwitz, Sigmund Abeles and others, under the tutelage of Skowhegan founder Henry Varnum Poor, juried by Jacob Lawrence, Ben Shahn and other prominent artists.

Ashley painting frescoed wall at South Solon Free Meeting House, Solon, Maine, 1956 (left) and Detail from fresco at the South Solon Free Meeting House (right)

1956-1958

University of FREIBURG

im BREISGAU

Ashley had always loved the German poets, having memorized many of Rilke’s poems in English. He wanted to learn the sound of Rilke’s words spoken in German. In 1957, Ashley headed to the University of Freiburg on a Fulbright grant. At first, Ashley felt isolated, until he found that the venders in the marketplace accepted him. He would sketch daily scenes of life in the marketplace, returning nightly to his room outside of Freiburg, where he would reinterpret his drawings in paint.

Freiburg Cathedral, drawing, ink on paper, 1958

1960-1973

New York

Upon returning from Germany, Ashley took a studio in the Bronx, near his family. He taught at nine or ten different institutions, including the Dalton School, Philadelphia College of Art, and Queens College. Ashley always sought ways to integrate art and poetry into curricula.

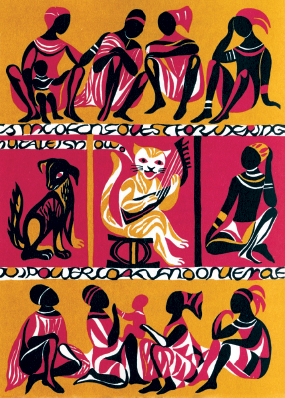

Jean Karl, an editor at Atheneum Books, visited Ashley’s studio in 1962 – the start of a nearly four decade-long relationship. Jean sent Ashley a contract to illustrate a collection of poems by Rabindranath Tagore: Moon, for What Do You Wait? Karl had been impressed by the variety of styles she saw in Ashley’s studio, “inspired by the cultures of the world.” In particular, she loved his three-colored African folktale illustrations – ochre, red and black - painted in tempera – evoking African sculptures, masks and rock paintings.

Images from The Adventures of Aku, Atheneum Books, 1976

1974-1988

The Dartmouth Years

From 1974-1988, Ashley joined the faculty of Dartmouth College’s newly established art department – just as Dartmouth was becoming co-ed. He eventually became head of “Visual Studies,” and he taught all levels of undergraduate courses in drawing, painting and design.Former student, Julie Miner, recalls the challenges faced by the charter class of Dartmouth women: “It was such an inspiration to see Ashley break down all kinds of barriers – race, gender, and even biases about art itself – in the most gentle way. He made a safe place for individual creativity at Dartmouth.”

Former Dartmouth student, Julie Miner, admiring puppets with Ashley during a painting workshop. September, 2013

1988-2000

The Cranberry Isles Years

Living and Creating on an Island

Ashley retired from Dartmouth in 1988. He winterized his house on Islesford and became a year-round resident of the Cranberry Isles. In his infinite quest to create art from “things cast off,” he recovered “treasures washed up by the sea,” on his daily walks. Ashley crafted more and more fantastic hand-held puppets from bones, shells, drift wood, fishing net, sea glass–held together with papier maché.

Ashley holding a puppet he made from bones and fishing net he found on the beaches of the Cranberry Isles, around 2012

During these years, Ashley dedicated himself to publishing numerous illustrated books in which he attempted to bring to life African tales, proverbs and especially spirituals—the songs of the African-American slaves whose only form of free expression was through these enduring popular songs that are rarely given appropriate attribution. Working tirelessly with his editor at Atheneum, Jean Karl, Ashley published ten books with Atheneum during this period, and he illustrated another eight books with other publishers.

Rocking Jerusalem and Let Us Break Bread Together, from Walking Together Children, Black American Spirtiuals, Volume One, currently available from Alazar Press, pub. 2012.

2001-2008

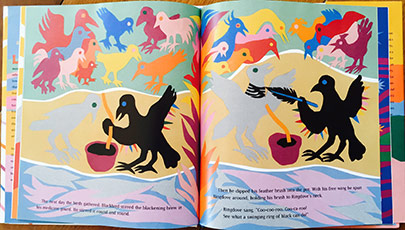

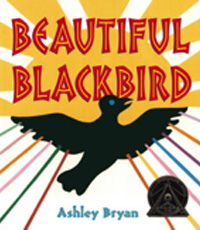

Beautiful Blackbird

Ashley’s new editor at Simon & Schuster/Atheneum, Caitlyn Dlouhy, encouraged him to develop one of the stories he had started working on with Jean Karl – a motif from a Zambian tale Ashley had begun with collage illustrations. His new editor loved the figures of the birds Ashley cut from colorful craft paper, using his mother’s sewing and needlepoint scissors. Beautiful Blackbird became one of Ashley’s most popular books, winning a Coretta Scott King Book Award in 2004.

Page (left) and cover(right) from Beautiful Blackbird, Atheneum Books, 2003. The Ashley Bryan Center chose Beautiful Blackbird as its symbol, because, like Blackbird, Ashley treats everyone as “family.” Blackbird represents Ashley’s deepest desire to kindle the creativity and celebrate the humanity within us all.

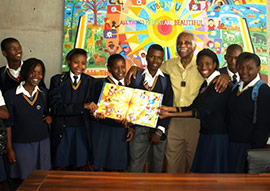

Supporting Programs in Africa

Ashley playing the recorder and singing spirituals with children at the Kiboya Primary School in Kenya, around 2008 (left), and Ashley posing with students in front of the welcome mural he created for the Ubuntu Pathways Centre’s reception in Cape Elizabeth, South Africa, around 2012 (right)

Ashley playing the recorder and singing spirituals with children at the Kiboya Primary School in Kenya, around 2008 (left), and Ashley posing with students in front of the welcome mural he created for the Ubuntu Pathways Centre’s reception in Cape Elizabeth, South Africa, around 2012 (right)

2008-2012

Receiving Recognition

2008 was a year of big awards! Let it Shine won Ashley his third Corretta Scott King Award for illustration, and later that year, Ashley was honored as a New York City Library Lion along with esteemed writers Salman Rushdie, Edward Albee and Nora Ephron.

With this recognition, it seemed that the award floodgates opened, as Ashley received the Laura Ingalls Wilder Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2009, followed by the Golden Kite Award for Nonfiction in 2010 for Words to My Life’s Song and the Coretta Scott King-Virginia Hamilton Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2012. Did he skip a year? No he did not! In 2011, Ashley received what he considers to be the greatest honor of his life—when the voters of the Cranberry Isles voted at town meeting to rename the school on his beloved Little Cranberry Island (also known as Islesford): The Ashley Bryan School. Ashley continues to visit the school regularly to read, teach, make art or just hang out with the kids.

Ashley with fellow New York City Library Lions award recipients, Salman Rushdie, Nora Ephron and Edward Albee, 2008 (left), and first day of school with a new sign for the Ashley Bryan School, 2012 (right)

Ashley and friend and fellow artist Henry Isaacs co-taught their first Islesford Labor Day Painting Workshop. These hugely popular retreats continued for 8 years.

2013

The Ashley Bryan Center

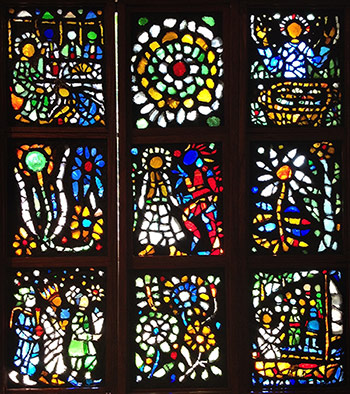

In 2013, a long-time dream of Ashley’s was realized when money was raised to install two sets of his sea glass panels in the Islesford Congregational Church.

This same year, a group of island friends and members of Ashley’s family decided it was time to do more to ensure Ashley’s legacy would continue for generations to come. The Ashley Bryan Center was founded with the mission "to preserve, celebrate, and share broadly artist Ashley Bryan’s work and his joy of discovery, invention, learning, and community.”

In the summer of 2014, the Ashley Bryan Center held a retrospective exhibition of Ashley Bryan’s life and work, displayed at the Islesford Museum, owned by the National Park Service, on Little Cranberry Island. “A Visit With Ashley Bryan” included a timeline of Ashley’s life with examples of his work in many media from various periods. It featured puppets, sea glass windows, paintings, drawings; and displays of book illustrations that used block prints, tempura paint, and collage. Many of the items had never been seen and much excitement was generated; over 12,000 visitors passed through that summer. The exhibit moved to College of the Atlantic, Bar Harbor, for the following winter and went on to the Wendell Gilley Museum in Southwest Harbor for the summer of 2015.

Sea glass panel from the exhibition

Many of the items had never before been seen by anyone but Ashley’s closest friends and family—in particular Ashley’s drawings of his war experiences in the segregated U.S. Army. Many people who thought they “knew” Ashley found they did not know about aspects of his life, the depth and breadth of his education and artistic experience. The exhibition proved to be very emotional and exciting for visitors—many of whom told their friends. The museum’s usual attendance of a few thousand visitors a summer expanded to over 12,000 visitors who came to see Ashley’s exhibition.

Page from Ashley's sketch book, pen and ink drawing, 1945, "Yesterday 140 Negro soldiers were taken off of homebound ships in LeHavre by the Navy because there were no accommodations provisions for segregation"

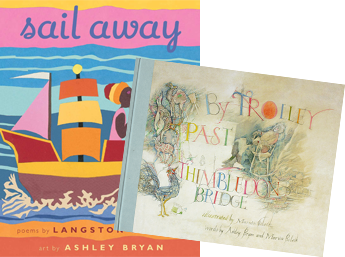

When it was over, friends at the nearby College of the Atlantic asked if the exhibition could be moved to the college for the winter, so the Center agreed to extend its life through February. Then the Wendell Gilley Museum in Southwest Harbor asked for a modified version of the exhibition to be displayed there for the summer of 2015. The exhibition was modified, and a new section, “Hot off the Press” was added to include the two new publications released in 2015: By Trolley Past Thimbledon Bridge, and Sail Away.

Ashley’s 2015 book releases

2016

Freedom Over Me

Ashley publishes Freedom Over Me, a finalist for the Kirkus Book Prize

August – Opening of the Storyteller Pavilion

2017

Awards and Exhibition

Freedom Over Me awarded Newbery Honor, Coretta Scott King Author Honor, and Boston Globe–Horn Book Award.

Exhibition at the High Museum of Art, Atlanta – “Painter and Poet: The Wonderful World of Ashey Bryan.”

2018

More Exhibitions

“Painter and Poet: The Wonderful World of Ashley Bryan” moves to the Portland Museum of Art in Maine.

Touring Exhibition organized by National Center for Children’s Illustrated Literature: “Our Voice: Celebrating the Coretta Scott King Awards.”

Exhibition at Ballard Institute for Puppetry, University of Connecticut: “Living Objects: African American Puppetry.”

I Am Loved published with Nikki Giovanni.

2019

Permanent Collection

Agreement reached with The Kislak Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, to house the majority of Ashley’s archive.

Ashley Publishes Blooming Beneath the Sun, illustrating poems by Christina Rossetti, and Infinite Hope, his World War II memoir.

Numerous print and recorded interviews relating to Ashley’s World War II experiences

On December 5, an evening at the Kislak Center was held to celebrate the gift of the archive and the launch of Infinite Hope with Ashley attending and speaking in conversation with ABC director, Nick Clark.

2020

The Morgan

The original preparatory work and final collages for Ashley’s book of Langston Hughes water poems, Sail Away, are gifted to the Morgan Library and Museum in New York. At the request of the Morgan, Ashley’s nephew Sidney Jackson did audio and video recordings of Ashley reciting the Hughes poems.

Infinite Hope receives Coretta Scott King Author Honor and a mention as one of four best non-fiction books at the Bologna Children’s Book Fair.

2022

Ashley Bryan died

in Sugarland, Texas, in 2022

Ashley's family held a celebration of his life on Wednesday, July 13, 2022 in the Town Field on Islesford. You can watch the video here: Ashley Bryan's Celebration of Life